The Approach of War

Before the war, there was an Equipment Department and a Station Design and Installation Department. S.D. & I.D. was based in London, under Mr. B. N. MacLarty, and it was responsible for the planning, design and installation of transmitters and also for the wiring and power supplies in studio premises.

The more technical aspects of the L.F. side of broadcasting were the responsibility of Equipment Department, which had a workshop that made the items (since at that time one could not purchase commercial equipment that was of a sufficiently high standard), and a small Designs Section under Mr. Colborn with about six engineers. Broadcasting House and the studios, as far as the lighting, heating and electrical cabling were concerned, were therefore the responsibility of SD& ID, but the technical equipment, microphones, amplifiers, switching and control room, and studio cubicle equipment, were the responsibility of Mr. Colborn's Designs Section.

Up to 1938, most of our regional premises, and Broadcasting House of course, were equipped with apparatus operating from batteries charged by mains-driven generators. The only mains operated studios were Bangor - a small studio centre with a control room operating from the mains via a large H.T. rectifier, supplied in duplicate, and L.T. rectifiers operated from two large transformers - and Maida Vale, which operated in a similar way. In addition there was the training school premises in Duchess Street which had a small control room and studios.

After the Munich crisis in 1938, steps were taken to devise an emergency control room in the basement of Broadcasting House, the original control room on the eighth floor clearly being vulnerable to bomb attacks.

In April 1939 the BBC bought Wood Norton Hall (seen here in 1960), near Evesham in Worcestershire and once the home of an exiled Duc d'Orleans. These premises were very secret; few people knew where they were - such knowledge must, I think, have been restricted to about a dozen people. We called it "Hogsnorton" after the mythical village created by the comedian Gillie Potter.

As far as Equipment Department at Avenue House was concerned, Mr. C. H. Colborn and Mr. Lock, who was Mr. Colborn's chief assistant designer, designed some rack-mounted OBA/8 amplifiers, called APM/1s (Amplifier Programme Meter). The OBA/8 amplifier, used for Outside Broadcasts, was a very versatile microphone-to-line-level amplifier with a main control on it. It had a four-channel mixer, the MX/18, associated with it. The new design made these into rack-mounted units, providing a single output for feeding to line and a monitoring output for feeding headphones. In order to make these usable in a control room, we needed some trap-valve amplifiers, and new designs, TV/17 and TV/18, were devised for the purpose. This equipment had been through the drawing office, it was being made but only a very small number, if any, had actually been delivered in the summer of 1939.

During August 1939 two or three of the Designs Section engineers were up at Broadcasting House with Equipment Department workshop staff working very hard and speedily to erect the temporary emergency control room. This was very tiny in area, I think about fifteen feet wide by twenty feet long, in what was, I believe, the fireman's room, next to the gallery of studio BA.

We were then going through the usual, very long-term, motions of schedules, drawings, collection of information for the installation, and the APM/1s, TV/17s and TV/18s, with apparatus bays, were all on order and were not scheduled for delivery for some months.

As I mentioned just now, one of the mains-operated control rooms was in the Training School premises in Duchess Street. These premises had, I think, three studios, a small control room of four bays and a small, six-channel, dramatic control panel. This, looked at in its entirety, formed a complete broadcasting unit and, on the Friday before war broke out (25th August 1939) Mr. Colborn came to me in some considerable haste, and it was unusual to see him hurrying, before lunch and asked me how long I thought it would take to remove the equipment at Duchess Street and re-install it in a secret place.

Now at that time we usually took about three months to install that sort of equipment, and that was provided we had all the drawings, plans, etc. ready. I said I thought that, with unlimited labour, we might be able to get it done in a month. Mr. Colborn went away, again in rather a hurry. After lunch, he came running back to me and said, "You must do this as soon as you can."

Equipment Department did not have a very large staff at that time and I found that almost all the manual workshop staff, mechanics and wiremen, were away doing emergency work in Broadcasting House and other places and that likewise most of the engineers had disappeared from their offices, presumably on special duties.

However, I found one engineer, Mr. Petrie, to assist in the dismantling of the equipment together with a wireman, a gardener and a general handyman. I then contracted two further wiremen from the Broadcasting House work and commandeered a large pantechnicon and driver from the garage at Avenue House.

We went that very afternoon to Duchess Street and started dismantling the control room and studios. We worked until l0 p.m. when I and the wiremen went home to sleep and left the engineer with the gardener and handyman to work through the night, dismantling the equipment.

Off to Wood Norton

At 8 am the next morning we loaded the pantechnicon and set off for "Hogsnorton." I was on a motorbike and the two wiremen were in a car. The senior wireman was the only one of us who knew the exact location of Wood Norton as he had been there in great secrecy to connect up a temporary installation in Steward's House. This consisted of OB equipment to provide three small studios, a tiny control room in the pantry, and lines to Evesham telephone exchange.

We got there at 3.15 p.m. and for the next week we worked all the hours that there were - we didn't move out of Wood Norton and we slept on the floor of the control room. One must remember in this connection that it was not just a matter of putting a mains lead on to this equipment. Eight bays of equipment had to be erected and wired. The L.T. Rectifiers and the two mains transformers had to be installed down in the cellar and heavy, lead-covered 7/.036 twin filament cables had to run from each rectifier back to each amplifier. These were not just soldered on; they had to be put on by lugs and with a blow-lamp, so it was no easy matter to terminate this sort of run of heavy lead-covered cabling. Similarly, all the H.T. leads were of single .036 lead-covered cable, and of course, 1-pr./10 was used for most of the programme circuits.

It may be of interest to realise that, until Wood Norton, the BBC always used single 1-pr./10 lead covered cable for all programme circuits, but when we came to install the Wood Norton control room, this cable was in rather short supply and, in order to cable the distribution frame to the jackfield we used, for feeding all the lines, a piece of 38-pair cable. This, to my knowledge, was the first time that a multicore cable had been used inside any BBC premises.

We were fortunate, in this instance, in having Mr. John Holmes, of BBC Lines Department, around the place, who told us how to connect up this quadded cable. I remember discussions taking place between myself, Mr. Holmes and Mr. Reggie Patrick (Assistant Engineer in Charge to Bruce Purslow), in which, although the BBC had always used individual lengths of 1pr./10 lead covered cable for all programme circuits, since a multicore 38-pair cable had been used by the Post Office from Evesham Exchange to Wood Norton there seemed to be no reason why we should not use this type of cable inside BBC premises provided it was balanced at both ends. This we did, the cable being provided by the goodness and courtesy of the Evesham P.O. I remember that from that day we used multicore cable increasingly in the Wood Norton installation, particularly for feeding programmes that we now refer to as 'ring-main' programmes.

For the main control position we used a large equipment cabinet from the training school, about 8' high and about 2'6" x 2'6", which we tipped on its side. The whole exercise was a very "make-do-and-mend" effort, and we put the dramatic control unit out of Duchess Street on top of this cabinet - this was the main control position! However, by Tuesday 5th September, we could have put out a programme from our lashed-up microphone on to the Post Office cables that were then terminated in the control room. From then on, we gradually tidied up the equipment and scrounged more - fortunately we had access to the wartime Avenue House emergency store hut, which was full of all sorts of devices, mostly raw materials, such as steel, brass, cable, wire, resistance wire, and we had the emergency workshops, so we had no bother on that side. Equipment gradually became available, and by November we began to receive the real wartime TV/17s, TV/18s and the rack-mounted APM/1s that had originally been ordered for installation at Wood Norton. As these became available, they were installed, and we slowly developed a comprehensive control and studio equipment.

A master clock was set up and adjusted on the control room wall. This was a pendulum clock normally adjusted by the manufacturer by the addition of tiny pieces of "silver paper" on the pendulum to get its effective length exactly right for accurate time keeping - no crystal controlled clocks or watches that we now take for granted!

Facilities were also arranged for recording programmes. In the early 30's the first sound recording equipment consisted of a large machine, known as the Blattnerphone, with reels about 2ft in diameter holding a little over a mile of steel tape capable of recording about 30 minutes of programme. These machines were later developed as the Marconi-Stille - an apparatus about the size of a sideboard still using the large reels of steel tape. The original machine found its way into a "museum" in Equipment Department.

In August 1939 Reggie Patrick, who had been involved in the installation and development of the original machine in Broadcasting House, was working in Equipment. He "disappeared" from his office in August and, in fact, had taken the recording machine out of the museum and was trying to get it operational at Wood Norton. This he succeeded in doing and, in fact, managed to make a recording of the Prime Minister's declaration of war.

The interior of the first mobile recording van, M53,

which entered service in 1935. It contained two MSS disc recording machines,

with facilities for levelling the turntables, and associated amplifiers

operating from a 24 volt battery.

From Sept 1939 the studios were in frequent use for Music, Schools Programmes, Features and Drama, these Departments having moved to Wood Norton in the first few days of the war, although they were later to move to Bristol, Bangor and Bedford.

The permanent equipment continued to be installed as it became available in early 1940 and Wood Norton became one of the largest broadcasting centres in Europe. According to Mr. B. Cox's 'History of Wood Norton' it was producing at its peak an output averaging 1300 programme items per week or about 835 hours of Broadcasting, most of it for various overseas services. News Agency information was provided by teleprinters associated with Press Association, British United Press, Exchange Telegraph and Reuters.

Other communication facilities included private lines to various Government Departments and to Fighter Command Main and Reserve RAF Headquarters. This was to receive instructions to close down various transmitters if required to prevent the Luftwaffe using BBC transmitters as direction finding aids on their air raids.

Life at Wood Norton

Wood Norton was a very secret place, no mention of it was made in any local or National paper and particularly no mention of the BBC.

No sleeping accommodation was available on the site, all the BBC staff were billeted in and around Evesham for which the people on whom they were billeted were paid a guinea (£1.05p) a week for board and lodging. Since, in those days, anyone from outside the immediate vicinity of Evesham was regarded as a "forriner", relations were sometimes rather strained between the townspeople and those forcibly billeted on them, who could not explain, due to the secret nature of the project, what they were doing at Wood Norton. This attitude was very much aggravated when real foreigners - Russians, Poles, Hungarians and other Europeans arrived to work in the monitoring service. Not all relationships were strained since it was in Evesham that I met my wife, who was a receptionist in the Northwick Arms, when I was billeted with her mother.

Life outside work was virtually confined to what was available in Evesham since the bus services were severely curtailed, the timing being such that it was not possible to get to Cheltenham or Worcester and back in a day. I was fond of walking a lot in Kent and Surrey, but around Evesham I found no footpaths and the only walking seemed to be through vast fields of cabbages and Brussels sprouts - both vegetables which I hate! One could go to the cinema, however. There were two in Evesham - the Regal and the Clifton. There was also an occasional dance in the Town Hall.

I was one of the first engineers at Wood Norton following the arrival of Bruce Purslow as Engineer-in-Charge in Easter 1939. He took up residence in the south lodge by the Golden Gates. These gates at the main entrance had come from another property once owned by the Duc d'Orleans - York House at Twickenham. The only brick buildings then on the site were - The Hall, Smith's Cottage, Steward's House, part of the Pear Tree complex and the restaurant complex which was then an open courtyard surrounded by stabling accommodation with a cowshed along the north east side of the courtyard. This cowshed formed our canteen and Bruce Purslow obtained a drinks licence for a bar. In 1940 the stable yard was roofed over to provide a much larger restaurant since the total staff, including Monitoring, by then exceeded a thousand.

In the beginning transport between Wood Norton and Evesham was by a quantity of bicycles, two small 150cc James motorcycles, one old Austin Twelve four seater saloon car and a shooting brake, the general idea was that any person wanting transport took whatever was available, drove it or rode it into Evesham and left it in the courtyard of the Northwick Arms. On return one went to the Northwick and took whatever was available. Never having driven anything as large as a shooting brake, I remember trying to drive it up Bridge St, with about half a dozen passengers when I stalled the engine and we ran backwards towards the Workman bridge till I managed to operate the hand brake! Some of the passengers wanted to walk back to Wood Norton.

Fortunately in Bruce Purslow we had an Engineer-in-Charge who was not very interested in red tape and who realised the urgent necessity of getting things done. When, for instance, we had to get equipment to the top of the hill, he went down to the town and purchased a tractor. The idea of doing anything like this without the necessary approvals, schemes and all the paper work was at that time very unorthodox; so was the fact that anybody who wanted to get to the top of the hill would drive the tractor up there!

A great debt is owed to Bruce Purslow, a colourful character and unorthodox engineer, for the satisfactory co-ordination and operation of Wood Norton at the outbreak of war. He encouraged and inspired everyone on the site to ensure the operation was a success. As an example, he encouraged the use of Christian names when this was not considered "correct". When petrol rationing was imminent, Bruce collected all the suitable containers he could find and had them filled with petrol for Wood Norton use. He encouraged anyone with innovative ideas, whether senior or junior, and was undoubtedly the right man for the job.

The Monitoring Service at Wood Norton

Reception equipment was located in two huts on the top of the hill, staffed mostly by engineers responsible for sending the signals to the two huts on the main compound which were staffed by foreign language monitors who recorded and transcribed the signals into English. There was another monitoring hut situated in the main compound. It's work was very secret; it was guarded by troops and was a 'Y' unit, monitoring morse and other transmissions in connection with Bletchley Park decoding work.

Recording equipment required for the Monitoring Service, where high quality sound was not so necessary, consisted of wax cylinders similar to those used in the very earliest "gramophones". These wax cylinders could be "shaved" and re-used.

The successful running of the teleprinter and communications side of monitoring owed a great deal to John Holmes and Jock Norwell, both from BBC Lines Dept, who went to Wood Norton in August 1939 to test the lines and then just "stayed there" for the duration, and in particular to a junior engineer from the small local telephone exchange - Maurice Hughes. He found himself responsible for PO/BBC work on lines and communications of national importance. He had no experience of teleprinters but rapidly learned to cope with the maintenance of them and became almost one of the BBC staff with the time he spent at Wood Norton. He was very willing to turn out at any time of the day or night to deal with emergencies and "acquire" for us any items of engineering equipment to assist us, conveniently forgetting the usual "red tape" associated with this, and his own hours of work.

Monitoring left Evesham in 1943, moving to Caversham Park, near Reading.

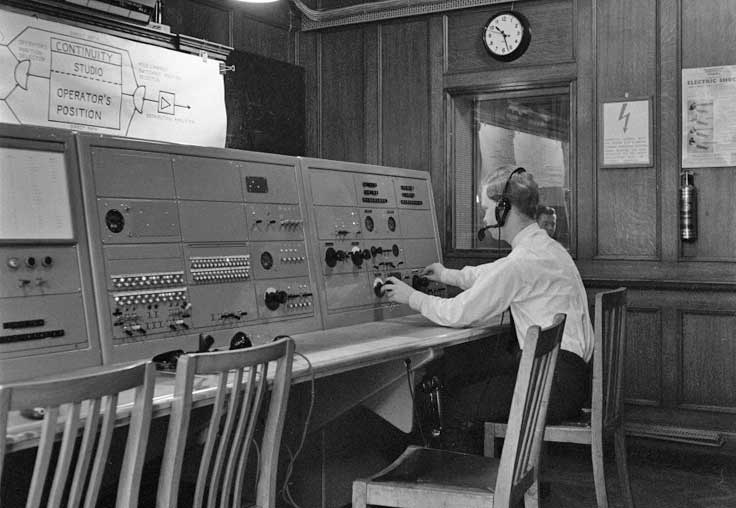

Continuity Suites

The idea of continuity working had been discussed in defining the relative responsibilities of the balance and control of musical programmes by musicians and the switching of programmes by engineers during the mid 1930s. This was further emphasised by the famous Tommy Woodroffe broadcast of "The Fleet's Lit Up" as part of the Coronation broadcasts in 1937. Although there was much discussion about it, the actual carrying out of the exercise, which relied on a very close co-operation between programme presentation people and engineers, really happened in the operation of the "Red" Network.

This was based in Abbey Manor, a large house between Wood Norton and Evesham owned by Squire Rudd. The BBC took over the house for the use of the Empire News Service in the spring or summer of 1940 and installed in there, I think, three studios and what we would now call a continuity suite. Out of this continuity suite the programme was fed down the line to Wood Norton control room for distribution to the S.B. network. It was the very great degree of close cooperation and discussion between Bruce Purslow as E.i.C. and Tom Chalmers as the Chief of the Presentation of the programmes which put into practice the close liaison between programme and engineering people, and those two gentlemen had the

Related page

The Fire

On the day of the fire at Wood Norton, 4th September 1940, I was enjoying a rare day off and on the road between Evesham and Wood Norton. I saw the smoke and hurried to the scene.

I mentioned, in the section about Continuities, a large house called Abbey Manor. It was owned by Squire Rudd who had a hobby of fire fighting. He owned an old London Fire Brigade solid-tyred fire engine, full uniforms with brass helmets for his staff and a silver helmet for himself. He had a private telephone line to the local telephone exchange and would be informed of any rick fire in the district, whereupon he and his male staff would set off in the fire engine driven by his chauffeur/handyman. The latter was the only member of the Squire's staff still in residence.

On my arrival at Wood Norton it appeared that the fire hydrants and hoses in the building were fed from a small pond halfway up the hill which had quickly been used up and the Evesham fire fighting equipment, in attendance, consisted only of a taxi towing a small trailer pump - this was a wartime arrangement provided in many small towns during the war and not of much use in fighting the Wood Norton blaze.

I immediately went back to Abbey Manor and found the chauffeur anxiously waiting to know if his fire engine could be of use. We quickly took it out and, with me ringing the bell on the engine, drove to Wood Norton. He took the engine across the fields to the nearby River Avon for a supply of water whilst I ran out the hoses up the drive from the Golden Gates. Being used to the location of Rick fires, away from a supply of water, there were ample lengths of hose and we soon had a better "squirt" than the Evesham fire fighters.

Soon fire fighting equipment arrived from Pershore and Worcester enabling the blaze to be got under control by about 1 am the next morning. We were of course very worried lest the fire should attract German bombers known to be in the vicinity and great efforts were made by all staff to rescue technical equipment, records, office furniture, filing cabinets, typewriters, etc. all of which would have been very difficult to replace in wartime. It was quite understandable in these circumstances that in their efforts to save a grand piano, staff not normally associated with orchestral activities should have sawn off the legs of the piano to get it out through a doorway not aware that the top was made to lift off the leg-framework for transportation!

Several Post Office circuits were put out of action but these were quickly restored and broadcasting was not interrupted except for an orchestral broadcast under the direction of Stanford Robinson which had to be cancelled. By about 2am the following morning, however, Wood Norton was able to give a tape reproduction of the broadcast via the emergency control room in the Steward's House.

The cause of the fire was never definitely known. The most likely explanation seems to have been that sunlight shining through a glass skylight had ignited insulation packing in the roof.

A temporary roof was soon constructed. This turned out to be not that temporary, as it survived until 1990 when the roof was reconstructed to the original design.

The Flood

Another notable incident which took place at Wood Norton during my period there was the flood. The Post Office had laid their usual 4" cable ducts down the main drive in the compound with manholes at suitable places - one opposite the Steward's House, for instance, one outside the control room and one opposite the monitoring huts. From this manhole a duct lead to a position under the monitoring hut and finished level with the ground. Cables then fed up a leg of the hut to terminate inside. From the manhole opposite the control room a duct led into the room through a hole about 18" above the floor since the control room floor was below the level of the manhole.

I was on duty that night, after a day or so of heavy rain, and heard a dripping sound from behind the equipment which was traced to water dripping from the duct. This was about 11 pm. We put a metal wastepaper bucket to catch the drips but these rapidly increased until water was coming out of the duct like two bath taps turned on. In spite of a relay of engineers with buckets etc.

Another storm brewing over Wood Norton in this 1983

photo by Peter Alcock

Order was restored the following day and the cause traced. Across the hill ran a dry ditch and this crossed the site of the monitoring huts. When these had been erected by a London contractor, unfamiliar with country ditches and drainage, the ditch had been filled in. Consequently when the heavy rain occurred the dry ditch, provided to drain the rainwater away from the Wood Norton site, overflowed when reaching the monitoring hut and then used the P.O duct under the hut as a natural drain. Unfortunately this led into the Control Room.

Some photos by Dave Edwards taken about 1960 show how little the atmosphere of Wood Norton had changed in the intervening years.

(above and right) The main building is hidden by

the trees on the left; as the signpost in front of the hut shows the dormitories

were out of shot on the right.

(Above) Beyond the main building a coach waits outside

the TV Hall, one of the post-war additions to the site. The coach provided

a regular service to the BBC Club and railway station in Evesham.

(Above) The main building on the left. Just beyond

it a road led to the exit. No pictures of that, but (left) a view

back to the entrance gates - at this time they were not the Golden Gates

mentioned by LG above.

(Below) A view of the Uniselector Control Room probably in 1962.

(Below) A view of the Uniselector Control Room probably in 1962.

Finally, some views from the air showing the site as it was about 1960 in the first shot and early 1970s (and showing the new Bredon Wing) in the other two.