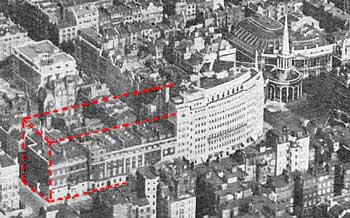

Nos. 10-22 Portland Place (marked in red above

and seen from gound level below.)

No.10 was the home of an old lady who would not

leave her house. This held up building for a number of years. No.12

was occupied by the Central Council for Schools Broadcasting. No.14

was the home of the Radio Times and a warren of passages ran between

this building and No.18. These passages lead to accommodation for OBs

Department, the Empire Service announcers (complete with sleeping quarters)

and Children's Hour. - G.S.

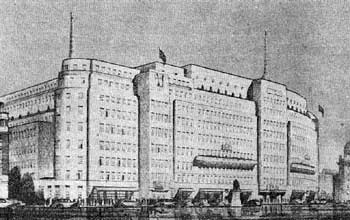

A special feature of the extended elevation was

to be the semi-circular treatment of the corner of Portland Place and

Duchess Street, surmounted by one of the masts removed from the existing

building. This shape was presumably meant to be an echo of the front

of BH. - G.S.

Excavation starting in 1939, showing the north-west

corner of the site.

Pressure on facilities in London led to the opening of five new studios and recording rooms in a former skating rink at Maida Vale in 1935 but this provided only temporary respite. A more radical solution was to extend Broadcasting House itself and in 1938 plans were unveiled for an architecturally impressive extension that would more than double the size of the building and provide new television studios conveniently located in central London. Dubbed 'London's New Radio City' and 'The Empire's Radio Centre', the proposed enlargement would have given Broadcasting House a far more balanced aspect than the cramped appearance it originally had (and still has to this day).

Site clearance was complete by the end of the year and contracts were let for excavating a huge 'tank' that would enclose five new underground studios and provide foundations for the new extension. Occupation of the entire building was scheduled for 1940, although in the event war broke out before construction work could begin. This grand new headquarters facility reflected the BBC's policy before the war, which had been to concentrate radio studio and control facilities at a small number of locations. This decision had to be reversed after the outbreak of war when the vulnerability to air raids was realised.

Contingency plans

In 1938 all public utilities and authorities embarked on air raid precaution measures and the BBC was no exception. Radio Pictorial magazine reported in May 1938 that preparations were well under way for gas-proofing the underground tunnels leading from Broadcasting House where, three floors below ground, the air conditioning pumps were being made gas-proof. The artesian well in the basement of Broadcasting House, although sealed, could be opened within half an hour and this would provide the continuous supply of filtered water necessary for producing oxygen by chemical means in the gas plant. A supply of anti-gas tents had also been purchased. What benefit these facilities subsequently provided is not known. The tunnel referred to is probably the one that led to the building called Egton House (now demolished). In a separate measure the BBC undertook a policy of dispersing departments to safer venues around the country.

The variety department went to Bangor in north Wales (where the County Theatre was used), a large proportion of entertainment staff to Bristol, drama department to Wood Norton, religious, music and Children's Hour personnel to Bristol and Bedford, research department to Bagley Croft (Oxon.), station design & installation to Droitwich, equipment department to Hampton (just outside Evesham), publications to Wembley and administration to Bletchington near Oxford. New studio facilities were established in Bangor, Bedford and Bristol. Aldenham Hall, near Elstree, Herts., was converted by the BBC from a country club into five studios for overseas services and also as a switching centre for programme distribution circuits for home and overseas listening. In spring 1939 and using an intermediary for secrecy, the BBC bought Wood Norton Hall in Worcestershire, once the home of the Duke of Orleans and later a preparatory school. Work was put in hand to convert the place into a self-contained broadcasting centre and monitoring station.

Going underground

At regional centres around the country subsidiary studio and control centres were provided in miniature a short distance away from the existing facilities. The same logic applied in London and in the search for protected underground accommodation, the BBC approached London Transport. Consideration was given first to the disused Drummond Street entrance to Euston station (Northern Line) in October 1940 but the BBC decided not to pursue this once a more radical scheme was conceived. Frank Pick, from 1933 to 1940 the Vice Chairman of London Transport, had taken a new post as Director General of the Ministry of Information (MoI) and in this role he wrote to his old colleague J.P. Thomas, recalled from retirement to take charge of tube shelter arrangements at London Transport. "A stroke of luck" is what he called the opportunity as the BBC now embraced a far more ambitious solution.

The BBC was now requesting the LPTB to drive two station-size tunnels northward from Oxford Circus towards Broadcasting House for studio and broadcasting purposes at its own expense. Pick could hardly contain his passion for the project since it could be tied in with the reconstruction of Oxford Circus station, "provided for free", and the MoI would support the scheme. For all of Pick's enthusiasm, this was not the opportunity that it appeared since London Transport had firm proposals for improving Oxford Circus that did not involve rebuilding practically the entire station and shortly afterwards the BBC was informed that "any low level tunnels built for the BBC will have to be entirely separate from any interests of the LPTB".

Plans drawn up by London Transport envisaged a tunnel of 26ft internal diameter with accommodation on two floors. It would lie 75 to 80ft below ground, with access by an 18ft diameter shaft and a 12ft emergency shaft. The BBC decided that it should lie below the part of the Broadcasting House extension site that had not yet been excavated (Site No. 2) and on 30th December 1940 the BBC's Civil Engineer wrote that the proposal seemed "highly probably to go ahead".

Change of plan - The Stronghold

The Stronghold was a complete broadcasting centre in

miniature built next to Broadcasting House during the war. In this view

dated November 1945 the 9ft 6in-thick concrete roof (removed later to

facilitate building the subsequent Broadcasting House extension) is

clearly visible. The picture, looking north-east with Duchess Street

on the left and Hallam Street on the right, shows protected air and

exhaust vents, with a rectangular vent into the corridor. The protected

porches have been removed but a temporary single-storey building is

visible, along with the much deeper shored excavation for the basement

of the abandoned pre-war extension scheme. It is just possible to make

out the low-level door at the bottom of the staircase, facing into the

excavation.

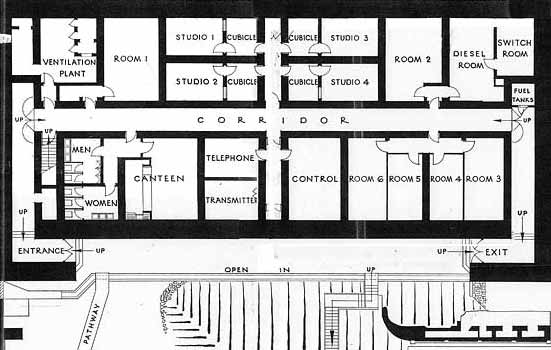

Known as 'The Stronghold' and first revealed to the public at large in the BBC Yearbook for 1946, this underground structure contained studios, recording rooms, a control room and offices, all under the shield of a concrete roof 9ft 6in thick. There was also a generator room and a small canteen, all laid out on either side of a spine corridor with gas doors and staircases for access at either end.

Inscription in the Stronghold,

photographed in 2002.

photographed in 2002.

In a once secret internal BBC memo it was noted

that the Ministry of Works had inspected the Stronghold and reported

that "...its chances of surviving an air burst bomb of the Nagasaki

type would be rated very high." - G.S.

The Stronghold figured as a kind of last resort, along with Wood Norton (Evesham) in the BBC's planned scheme for evacuating studios. According to a document entitled 'Emergency Evacuation of London Premises' undated but almost certainly prepared in October 1942:

"The Stronghold and premises at Evesham are general reserves for all services. Within the limits of accommodation and facilities available, the Stronghold is a last reserve for any or all of the Corporation's services. It is also equipped so that Home News, News Talks and Presentation, could transfer to the Stronghold as soon as News Agency and Recording facilities were provided. (The Stronghold is reached through the gas-proof door, LG2, opposite the Lounge, on the lower-ground floor in the north-east corner of Broadcasting House. Keys are in the possession of the Duty Officer, Duty Room, B.23). Moves to Evesham or the Stronghold will be decided by the Director-General in the light of prevailing circumstances."A total of 10,000 tons of concrete was used in the Stronghold's construction and it was designed from the outset to allow an extension of Broadcasting House to be built above later on. That said, it was an awkward structure to incorporate into later construction as the Stronghold is somewhat deeper than the lower ground level of Broadcasting House (one floor down from the ground floor and in fact above the level of the basement studios) but above the level of the basement of the 1960s BH Extension as eventually constructed. Built into the Stronghold was a door with a staircase leading down and ending in a brick wall, intended to give access to the basement level of the Broadcasting House extension originally intended.

The latter was finally opened in 1962, although not to the elegant designs of 1938 nor on exactly the same alignment. The way into the Stronghold was through the lower ground floor of the 1960s extension building, although when originally constructed it stood on its own, outside the confines of Broadcasting House.

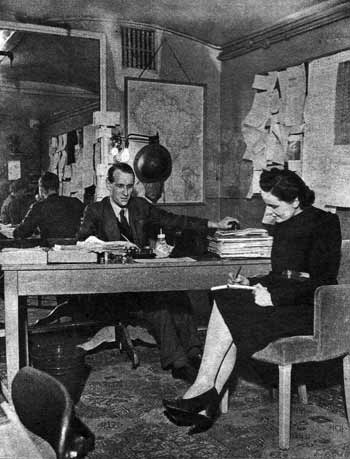

Working conditions in the Stronghold are not recorded, possibly because it saw little actual use during the war.

Roy Hayward worked as a Junior Maintenance Engineer (JME) in London Control Room (LCR) at Broadcasting House from 1942 to 1943. He recalled:

"We were not brought into contact with the Stronghold at all and we were told it was to be the new, bomb-proof control room of the future. I do, however, remember that I used to park my bicycle in the entrance to the Stronghold alongside a few cars and motorcycles that were using the space for parking. This was on the east side of Broadcasting House in Hallam Street, where there was a sort of slope down from the road level into the depths. The slope was shut off by temporary doors or barricades several yards in from the road and I seem to recall a low wall beside the pavement enclosing the parking space in front of this slope. It was, of course, a building site and as such we were not told much about its purpose. I believe there was a large double-door entrance to BH next to the low wall that was used for the catering dept and other deliveries. It was a tradesmen's entrance I suppose and used on one occasion I believe for admitting the King and Queen (or is that apocryphal make-believe?) Nobody I knew ever visited the Stronghold in my day and the place did not come up in conversation at all. We were reticent to enquire about things we did not understand as the war was on."Incidentally, the Stronghold is the same protected accommodation that Peter Laurie described in Beneath The City Streets but mistakenly assumed to be at the Maida Vale studios.

Protected cables

The Post Office had an obvious role providing many essential lines and facilities to the Stronghold and to BH, both for internal communication and for taking broadcast programmes from the studio to the transmitters. It is reasonable, therefore, to assume that a cable route was provided at deep level for this purpose.

Rumours abound within the BBC of a tunnel connection to the Bakerloo Line of the London underground, which runs so close that the rumble of trains is frequently heard in talk programmes on Radio Four. Searches of the BBC, BT and London Transport archives turned up nothing to confirm this speculation but a letter in the BBC's Prospero magazine for retired staff in 2002 lent considerable support in favour of this contention. The letter's writer was

Related page

It is still unclear whether the cable connection to the tube tunnels ran direct from the Stronghold or via the sub-basement of Broadcasting House but the former is more likely. Mr Smith understood a simple pipe connection was used and this would accord with the 12-inch bore steel pipe connections provided for cables from the War Office and Air Ministry buildings to the Whitehall cable tunnel system.

It is unlikely that the tube connection is still in use but its application was certainly foreseen during the Cold War. Treasury files at the Public Record Office discussing the BBC's planning to ensure broadcasts in the face of any future hostilities are one such place where this scheme is mentioned. The notes of a meeting held 12th March 1954 to discuss capital expenditure on civil defence include mention of financial provision to be made for "links between the BBC citadel in London and the Post Office deep-level cable system". A sidelight appears in a minute written 24th May 1954 by a BBC official: "While these [deep level cable] tunnels are not at a sufficient depth to safeguard against a hydrogen bomb exploding above, they would afford protection under other circumstances."

Four months later a BBC report to the Treasury set out 'the BBC Deep Level scheme' stating that plans had been made to connect the BBC Stronghold to the Post Office deep-level cable tunnels, involving the sinking of a shaft from the Stronghold to the Bakerloo Line at a cost of £56,000. Although not stated in the document, the cables would run southbound and connect with the Post Office network at Trafalgar Square. The BBC looked to the government for a decision and again sought advice the following year in view of the increased threat from the Soviet H-bomb. Although another note in the same file said the 'deep-level outlet scheme' had been abandoned in July 1955, this did not end the matter. A later document of 31st January 1957, relating to an internal Treasury review of the BBC's proposed civil defence expenditure plans for 1957/58, says under the heading Deep Level Outlet:

"There seems to be some mystery about this. This was, I believe, a scheme to connect the BBC stronghold with the GPO deep level communications system in London. The project was planned with the Post Office and was to be undertaken by them. It was originally expected to cost £36,000 (a figure of £20,000 has also been mentioned) but was abandoned in July 1955. We do not know why £5,000 was included as 1956-57 expenditure. Nothing has been spent up to 30th September 1956."There is no factual evidence whether this new cable scheme was ever built. The BBC's written archives have not been able to trace any information and whilst British Telecom would know if it had laid cables in such a tunnel, it does not discuss matters relating to customers' private installations, meaning that the later history of the Deep Level Outlet remains an enigma.

More subterranean studios

Returning to World War II, the Stronghold was not the BBC's sole underground accommodation in central London. The growth of overseas broadcasting for presenting credible news reports and entertaining British forces abroad brought an urgent need for additional studio accommodation, preferably protected to avoid disruption by enemy bombing.

Among these were the Criterion Theatre (Piccadilly Circus), the Paris and Monseigneur news theatres (half way down Lower Regent street on the east side and Marble Arch respectively) and a studio at Bush House belonging to the J. Walter Thompson advertising agency. All of these were underground and hence considered 'security areas'.

The Bush House studio of J. Walter Thompson had been opened in 1937 and was built specially for recording sponsored programmes broadcast on commercial stations such as Radio Luxembourg and Radio Normandy that sidestepped the BBC monopoly before the war, broadcasting popular programming to Britain. It had been designed along the latest principles with no expense spared and was built below the building above a former basement swimming pool (its ceiling is a few feet below pavement level). The studio was acquired by the BBC in September 1940 and subsequently between January 1941 and March 1942 considerably more accommodation in Bush House (not all underground) was taken by the BBC. By the end of the war there were 15 studios in the building, which remained for sixty-odd years the hub of the BBC's World Service.

However, by far the most significant below-ground studio complex of the BBC during the war was at 200 Oxford Street, where the east block of Peter Robinson's department store was requisitioned in June 1941 for the BBC's overseas services (see endnote). Known operationally as the 'PR Building', the actual studios and control room were 50 feet below ground level in the basement, protected by heavy steel reinforcement applied to the floor and ceiling of the ground floor. Considered opinion has it that the studio had lines to Broadcasting House connected via the Central Line tube tunnels and Oxford Circus.

Creating a studio centre from scratch under war conditions was an immense challenge but one to which BBC engineers responded with a degree of flexibility which managed to combine a utilitarian approach with a touch of imagination and engineering memory. L. G. Smith, mentioned above, was the engineer responsible for the planning and installation of the control room and studio equipment. He states:

"Before the war an installation of this size would have taken years rather than months since all equipment and interconnecting cables would have been individually designed. This was quite unacceptable in wartime. Many components were unobtainable; studio cubicle desks were made from office tables with plywood backs and sides. Microphone stands were derived from electric conduit components. Shortage of components was not the only problem; all circuits were lost when rats found their way into the microphone skirtings and bit through the lead covered cables to get at the wax inside. Nevertheless the whole installation, commenced in December 1941, was handed over for service for Overseas Programmes during May and June 1942."For many reasons the PR Building was not an ideal location for broadcasting. Conditions were cramped, ventilation was poor and noise from passing trains was clearly audible on programmes. Pawley's official history of BBC engineering also mentions that the studios at 200 Oxford Street were so close to the tube tracks that the performers' ribbon microphones picked up a high-pitched hum caused by harmonics of rotary converter noise carried on the conductor rails.

One more underground (in both senses of the word) radio studio was that of ABSIE, the American Broadcasting Station in Europe. Operated under the auspices of the U.S. Office of War Information, this station went on air on 30th April 1944 as part of the Allied preparations for the invasion of Europe. Technical assistance was provided by the BBC, with a studio centre underneath the Gaumont-British offices at Film House, 142 Wardour Street in Soho. The station broadcast news, talk and music in many different European languages to promote the Allied message, initially to prepare the people of occupied Europe for liberation, then after D Day to incite the foreign workers in Germany to sabotage the German war effort and finally, as the war neared its end, to urge the German people and armed forces to surrender.

ABSIE came to some prominence as the station that broadcast the remarkable 'lost' broadcasts in which the Glenn Miller Band broadcast in German to the Wehrmacht. The programmes were recorded at EMI's Abbey Road studios and introduced in German, with Miller himself reading from a phonetic script. Six half-hour programmes were recorded by the band and broadcast on Wednesdays starting 8th November 1944 as Musik für die Wehrmacht (Music for the Wehrmacht).

ENH identified

Mention was made of ENH, the BBC's wartime emergency news studio in Finchley. Its location was a private residence by the name of Kelvedon in Woodside Avenue, Finchley, N12. Houses in this road were not numbered in those days but a street directory indicates that Kelvedon was on the west side, the sixth house counting from the south end of the street. Roy Hayward (mentioned earlier) remembers and he recalls how he and his colleagues were required to take spending a night shift of four consecutive nights at ENH.

"Emergency News House was in the basement of a very anonymous looking but large Victorian house, set back from the road in its own splendid grounds at Woodside Park near Finchley in north London. It was rumoured that the house was 'allocated' to the Chief Engineer, Mr P. A. Florence, but I am not sure of this and I never saw anyone who lived in the house. It was permanently manned 24 hours a day by four engineers following the four control room shifts A, B, C and D and the same shift hour patterns.Wartime broadcasting strategies

"It was described to us as a place that could be used to continue broadcasting to the nation should BH become devastated by bombing. There were two studios, one of small 'news reader' size with a control cubicle underground in the basement, and another on the ground floor that was probably the drawing room of the house. It looked out over the garden through French doors and contained little furniture except for a middle-sized Challen baby grand piano. Underground in the basement was a control room - a long room with bays of jackfields and amplifiers carrying probably every network and programme service out of London. A small loudspeaker hung on the end wall and it was usually plugged during the night for us to hear Red Network being broadcast from 200 Oxford Street to America (I recall hearing Ed Murrow on several nights).

"There was an emergency electricity power and lighting Lister diesel generator that we were required to run up just before 06.00. I always thought that this time had been specially chosen to wake up the chief engineer upstairs and not before - but then we were very young! We were also required to do a full test on all the studio equipment and, on a nice early summer's morning after the test, I would put a mic out into the garden and relay to my shift brethren in LCR in the sub-basement of BH, the sounds of the dawn chorus. Other JMEs, more musically accomplished than me, would play that Baby Grand piano quietly!

"There was also another ENH located in the basement of a block of expensive flats in Grosvenor Square, diagonally across the square from the American Embassy. This was a single, unattended studio. It was always tested about 05.30 about once a month. The Senior Control Room Engineer would give one of the JMEs the keys to the entrance of the block of flats and the studio door, which was two floors down in the lift. The studio would be already plugged at the 'Lines incoming' bay in LCR to a bay position and all the routine testing of the mic, the mic leads, the plug in the wall, the clock, the lights and the TD/7 record turntable (Teddy Bear's Picnic, the BBC's standard test record, was in the rack) would be done and, before switching off the power, a ring on the internal telephone to test it and to correct the clock time if necessary and finally check that all was well with the test. Then it would be a rush to catch the 73 bus along Oxford Street to Oxford Circus and report back to the SCRE to hand in the keys and sign that the studio had been tested. I can only remember doing this about three times in the three years I was in LCR. Perhaps it was taken out of service eventually. Then again we JMEs were not supposed to know everything that was happening-there was a war going on!"

Broadcasting of course played a vital role keeping the population informed during the war. Protecting the studios and means of making programmes was one thing; making sure they were heard was another and this meant ensuring that they went out over the airwaves. Under peacetime conditions the most cost-effective means of broadcasting is to use a small number of high-power transmitters covering as broad an area as possible. In war the vulnerability of this approach was obvious; relatively limited enemy action against the handful of transmitters could silence the BBC and eliminate the government's direct link to the population at large. Worse, this small number of powerful radio stations could act very effectively as homing beacons for enemy aircraft.

An alternative strategy was needed and a decision was taken at very high level to establish a secondary network of low-power transmitters scattered across the country that would not assist the aggressor and could maintain transmissions if the high-powered stations were taken off the air at the instruction of Fighter Command when air raids were expected. Known as the H Group stations, these had a range of about 10 miles around and the intention was that under normal circumstances they would relay normal BBC programmes but they could also be operated by local authorities or Regional Commissioners to broadcast special bulletins and instructions if they were cut off from central government.

Work started on establishing these stations in autumn 1940 and although this put great strain on engineering resources, by the following year some 60 had been put into service, with a few more following down to 1944. Most of them were erected on municipal property, with transmitter and control equipment generally protected or underground and equipped with aerials slung from water towers or industrial chimneystacks. The system worked remarkably satisfactorily, even during the heaviest air raids of 1940.

Geoff Leonard, who started his BBC career in 1941 explains:

"The 'H' Group transmitters were a chain of sixty low power medium wave transmitters varying from 100 watts to 300 watts and all transmitting the Home Service on the same wavelength of 203 metres. They served a dual purpose. First, they didn't have to be closed down on the approach of enemy aircraft, because their range was reputedly only a few miles (although each transmitter carried out a test transmission once a month, according to a schedule, so that Tatsfield, the BBC's monitoring station, could check the accuracy of the frequency of transmission and make sure it had not drifted). Sixty transmitters not quite on the same wavelength would have made reception horrible with superheterodyne whistles. The second purpose was to provide regional devolved governments a voice to the local population in the event of a breakdown of central control. Many of these stations were kept on as part of the post war civil defence arrangements."Planning for invasion

Very adequate details of the construction and operation of the H Group network are given in books by Pawley and Wood. What is not mentioned at all, however, is the secret preparation for broadcasting messages to support organised resistance groups in case of invasion. The term 'stronghold' appears for a second time now in the title Operation Stronghold given to this operation.

It was, an article in The Independent dated 2nd May 2000 revealed, nothing less than a plan for a network of 'guerrilla radio stations' that would operate in the case of invasion. The BBC's Studio & Equipment Committee had the task of setting up emergency studios fully equipped and ready to operate at any moment. Furthermore, in the event of invasion the idea was to put well-known voices on the wireless. People such as the announcer Alvar Lidell and the eminent novelist and playwright J.B. Priestley (at that time one of the most prolific broadcasters) would have given instructions to the population, whether to resist, what to sabotage and so on. So says the article.

In London, Broadcasting House was to be abandoned for the basement of 200 Oxford Street before the broadcasters retreated to other BBC studio locations such as Maida Vale, Bush House, Aldenham or Wood Norton. Should these be overrun, the secret regional emergency studios that had been created hastily from nothing were to be activated. Housed in a mixture of private homes, schoolrooms and meeting places, they were as follows:

London: Methodist Missionary Society Building (25 Marylebone Road) plus 55/57 Portland Place.Geoff Leonard, who was based in the BBC Control Room in Birmingham during the war years, recalled:

Midland: Kidderminster (a large house called The Elms and the New Meeting Hall)

North East: Ponteland, near Newcastle (Methodist Church School)

North West: Penketh, near Manchester (Greenbank)

Scotland, east: Edinburgh (11 Newbattle Terrace)

Scotland, west: Glasgow (225 Hamilton Road)

Wales: Aberdare (the Constitutional Club)

"I used to have to take my turn in going to the emergency studio centre at Kidderminster. This was a large private house in its own grounds. There was a very small control room and three studios, all nicely done out in a pale yellow wall wash, and with a microphone table and a Type A ribbon microphone in each. The chore was to switch everything on and do a voice test from each. It made a nice afternoon out!"Another young engineer who spent some time doing Comms work around Glasgow recalled that every week or so they used to go to a house on the outskirts of Glasgow which had lines routed through it so they could be bypassed or programmes inserted. Presumably this was 225 Hamilton Road.

The minutes of the Studio Equipment Committee meetings show how the new stations were requisitioned and fitted out. Much of the work was in hand by May 1942 and nearly all work on the scheme was complete by the autumn. At the end of the war they were returned to their original condition, with most vacated already by the end of 1945. Mr Bennett-Levy, the collector and dealer who bought these papers at auction, said:

"Nobody knew about this at all; it was kept hush-hush. No-one would ever admit that the possibility of being invaded and conquered was very real. All these studios were meticulously returned to their original condition, so no clues were left that these studios had ever been made up."Precautionary constructions such as these provided for use in national emergencies are known as Deferred Facilities or 'DF projects' within the BBC. Within the Post Office and BT they are termed Deferred Services but the context is identical.

Old plans for a new war

Consideration of broadcasting under wartime conditions, happily abandoned with the end of hostilities in 1945, was hastily renewed with the advent of the Cold War. The position in 1957 was little changed, however, with plans in place for national coverage of two programmes on medium wave plus separate coverage for Wales and Northern Ireland coupled with Scotland. Just as in World War II, the high power medium wave transmitters would operate in synchronised groups, subject to closure on instruction from Fighter Command. Out of a network of low-power medium wave stations, not subject to closure, 54 of the 73 planned stations had been installed but installation of the remaining 19 had been stopped pending a revised scheme for wartime broadcasting that would enable civil defence regional broadcasting.

Known as Wartime Broadcasting System (WTBS) and devised by the government in conjunction with the BBC, this new scheme was intended to maintain a radio service for informing the public during national emergency. The BBC report Home Sound Broadcasting in War dated July 1957 clarifies that the nucleus would remain in London, operating from the Stronghold until it becomes untenable or the seat of government leaves London. WTBS was thus seen to form an integral part of the government's civil defence strategy and in the event of hostilities would provide a single national programme of news and information during the transition to war period and post-attack.

ENDNOTES

London's New Radio City - a contemporary description of the Broadcasting House extension that never was.

Excavation of the Portland Place site upon which Broadcasting House will be extended to more than double its current size is to begin in early 1939. More than a million cubic yards of earth will be removed and the depth to which the building will go - 54ft below pavement level - will be lower than the vaults of the Bank of England. Broadcasting House is probably London's deepest building. So large will be the volume of the pit, from which the superstructure will ultimately rise that it would have a capacity of nearly ten million gallons of water.

The architects are Messrs Val. Myer and Watson-Hart, FFRIBA, and Messrs. Wimperis, Simpson & Guthrie, FFRIBA, in association with Mr M. T. Tudsbery, MInstCE, the Civil Engineer to the Corporation. Messrs Higgs and Hill Ltd have been awarded the contract for the excavation and for the erection of retaining walls around the site, which has already been cleared. The work will be complete by about the middle of next year. Soon afterwards work will begin on the construction of the new building, which it is hoped will be ready for occupation by the end of 1940. This work will be the subject of a later contract.

The first stage of the present work will be the opening of a trench around the site, some thirty feet wide and fifty-four feet deep, in which self-supporting retaining walls will be constructed to withstand all external pressure. Asphalt will face these walls and will be returned, beneath them, and laid over the whole of the site. Five feet of 'loading concrete' will be superimposed upon it. The main structure, therefore, will virtually be built into a huge 'tank'.

The lower part of the tank below the standing level of subsoil water, a fact which will demand special measures to ensure that the asphalt seal is perfect at the junction of the new tank with that of the existing building, to compensate for settlement when the weight of the new building comes to be taken upon the foundations. The site area at ground floor level is 20,950 square feet, compared with 17,390 square feet of the existing building.

The elevation - one of five schemes submitted - has been approved by the Royal Fine Art Commission. The architectural treatment of the extension will continue and amplify that of the existing facade to Portland Place, the two portions of the building forming a complete architectural entity that will be both dignified and in harmony with its surroundings.

Five underground studios will be incorporated in the extension, and, in order to eliminate all possible risk of extraneous noise, each will be constructed as a separate shell, floated and isolated from the building itself. A General Purposes studio will be 80ft long, 54ft wide and 30ft high. Three Dramatic studios, an'Effects' studio and a number of rehearsal rooms are also being provided.

Above ground-floor level the extension is designed as an office building, with rather more accommodation than Broadcasting House has at present. A Control Room suite will be situated on the seventh floor and this will be in addition to the present Control Room. On the sixth floor will be a Staff Rest Room, while a restaurant with accommodation for nearly three hundred people is to be built on the top (eighth) floor. A light court will occupy the centre of the extension above first floor level; the building itself will have a maximum height of approximately 110 feet.

Department stores as offices

It was noted earlier that the BBC took over part of the Peter Robinson department store for office and studio accommodation. In fact the building also served as overflow accommodation for COSSAC, mentioned in Chapter 6. This was not a unique arrangement, either. The Air Ministry occupied part of the Harvey Nichols building, whilst the India Office took part of the Peter Jones department store. The U.S Headquarters Air Service Command occupied part of the John Lewis building.

Text by Andrew Emmerson, very slightly adapted from a chapter in his book 'London's Secret Tubes' published by Capital Transport Publishing.

Les "LG" Smith provides this footnote:-

At the time the Stronghold was built considerable thought was given to ensure that it could be incorporated into the BH Extension as it was being planned in 1937/8. My understanding was that the position of the Stronghold was that planned for the cashiers' office, which would require secure concrete walls similar to the construction of banks. The foundations of the Stronghold were planned to support the weight of the proposed superstructure of the Extension and consisted of 58 cored piles. The roof of the stronghold was augmented by a top layer of concrete blocks about 4x4x4 ft. with lifting eyes built into them so that they could be easily removed after the war.

The Stronghold corridor in 2002.

More photos on next page.

More photos on next page.