With my JME friend as guide, I walked to MV to report for the morning shift at 8am. From the front entrance he took me down a steep flight of stairs to a basement, and then along a seemingly unending gloomy corridor which was dimly lit by naked pendant 40 watt bulbs, to the Recording Section. Welcomed by the SRE, I met my new colleagues, two REs and a WO whom I recognised from the training school. An RE then took me on a guided tour, beginning 'upstairs', the ground floor.

Returning downstairs to our basement work area, the contrast was striking. A few patches of flaking white paint probably applied decades ago, still clung to the exposed blackened brickwork. Along two walls were continuous runs of large 1930s cast iron pipes which carried hot and cold water to the whole building from the Boiler Room which blocked the end of our corridor. Parallel to these were new hastily applied lengths of conduit carrying the vital power cables and communication lines. Unpainted brick walls divided a succession of spaces which had been roughly partitioned by boarding to make rooms. The RE took me along the corridor and introduced me to the occupants of these spaces. At the staircase end was our local Control Room, directly connected to the one at BH and continuously 'manned' by a CE and a couple of WOs. Next was a sort of First Aid room with basic necessities and an adjacent cubicle with four bunks.

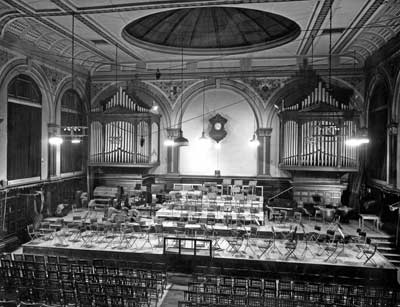

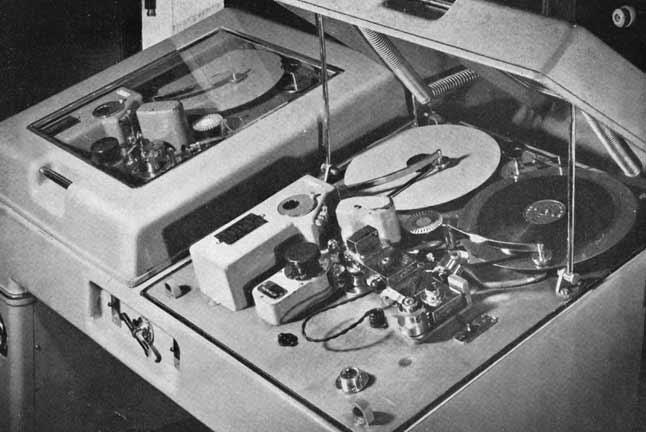

The next two spaces were a hive of industry. Floor to ceiling storage racks were packed with replacement parts and at wooden benches cluttered with electrical components several JMEs were wielding soldering irons. This was the Maintenance Engineers' area. Their task was to repair or recycle and reuse if possible the components of any bit of equipment which was not operating correctly. Everything was in short supply. Finally we reached the Recording Section where it was obvious that 'things had been done in a hurry'. When the first bomb hit BH in 1940, Maida Vale, thought to be a less conspicuous target, was hastily brought into use. In the first partitioned room were two disc recorders and a group of playback turntables. The second housed two adjacent Marconi-Stille tape recorders. The third contained a Philips Miller film recorder and in the fourth space, ranks of shelving were equipped to store completed reels of steel tape, film and discs. In each recording room was the universal metal rack housing the grey metal boxes containing amplifiers and other electronics. Terminals with jacks connected incoming and outgoing material with studios or the Control Room. The BBC's 'fail safe' policy was to have two identical units next to each each other.

Switches enabled instant transfer from one recorder to the other one if it was noticed that the newly recorded sound was losing some quality. This quick action caused only a barely noticeable blip in the recorded sound. A yell along the corridor brought an ME to check or replace the offender.

Furniture in each recording room consisted of a wooden trestle table, a scattering of cheap wood folding chairs and a large free standing loud speaker with remarkably good sound quality. The SRE, our only contact with the outside world, had a telephone on his table and on the wall above was a notice board pinned with a variety of typed 'Instructions'. One faded slip of paper said 'The nearest public shelter is 100 yards along Delaware Road.' Another amusing one said 'Do not bore us with your bomb story - yours was no worse than ours.'

During our tour, my guide had enlightened me about engineers' status in the BBC hierarchy. Directors, producers, broadcasters, announcers, actors and musicians were the Upstairs People whom we would seldom see except on our daily visits to the canteen. We were the Downstairs People, the Nibelungs, who simply carried out instructions sent from above. Upstairs People never visited our dungeon.

Every morning the SRE received by internal post a typed document which was that day's Recording Schedule. He allocated each one of the day's tasks to the person with experience of the medium needed, disc, film or tape but most important was the specified deadline. Recordings needed for News bulletins took priority. We WOs got the less urgent stuff. Thus, on that first morning I was introduced to 'The Front Line Family" the first BBC soap opera. Recorded daily on disc, this recounted the daily life of a 'typical plucky British family'. Home each evening after his day job making planes, Mr Robinson donned his Home Guard uniform and went to defend the country against invasion. Mrs Robinson, an expert at managing the rations, also did First Aid and ran a canteen for Service men and the Women's Voluntary Service Rest Centre for those bombed out. One daughter Mary was in the WAAF, the other in the WRNs, and of course their son Andy was a Spitfire pilot. This stuff fortunately was never heard on our Home or Forces services but complete recordings of every week's installments were sent off speedily to the US networks who were apparently greedy for them. The Family were in fact actors script reading in one of the studios above us but when they began to receive parcels of food and candy, they became aware that people in the US believed them to be a real family. Some of the goodies even found their way downstairs. We also acquired an addiction to this 'soap'. Having left Andy crashing to the ground in his Spitfire, returning on shift after two days off one's first question was "Did Andy get out in time?" "Of course," would be the reply.

The Marconi-Stille RecorderTwo weeks later, I moved to the evening shift, 4pm to midnight. I was delighted when an RE was told to teach me the use of the tape and film recorders. We began with the Marconi-Stille tape recorder.

Next in the row were two recording heads. Through the coils of their pole pieces was fed a direct current the opposite in polarity of that of the saturating head, and superimposed on this was the alternating current of the incoming sound signal. These electro-magnetised pole pieces, in continuous knife edged contact with the moving steel tape, transferred the magnetic impulses to the tape where they were retained. Last in the row of heads was a reproducing head. Switching occasionally between this head and one of the recording heads enabled the monitoring of any contrast between the incoming and recorded sound quality while recording was in progress. Finally the spool of tape was rewound at twice the speed, back to the start position before subsequent playback by the reproducing head. To compensate for the relative increasing and decreasing weight of the two heavy spools and maintain constant tape speed, behind a sheet of protective glass, loops of tape were allowed to form and make momentary electrical contact with a complex mechanism and this then appropriately adjusted the required speed of both spools.

This cumbersome method of recording was an early BBC experiment with the medium and the first machine was installed in 1935. It still satisfied the need to record programmes lasting an hour or more. With a 30 minute interval between change-overs to the adjacent machine, a suitable moment for this could be pre-planned. After even just one play back, the medium was ready immediately for follow on recording. Its sound quality covered the same frequency range as disc and remained constant, unlike disc where due to the compression of the sound track in the smaller circle near the centre of the disc, the higher frequencies could become unplayable by the stylus.

Tape machines were thus useful for comedy, drama and the more routine music programmes and as a back-up to disc and film on important occasions. Tape occasionally broke or needed to have a section edited out. Fortunately a rare event, this involved overlapping the two cut ends and electrically spot-welding them together. The primitive gadget used for this job resembled one's grandmother's treadle sewing machine. The overlapping ends were placed under an electrically heated tool which, moving up and down, melted a spot of metal on each contact. To produce this vertical action we pounded the treadle rapidly with both feet until the entire area of metal had been spot welded. Finally, with a workshop file we filed and filed the joint down until it could pass smoothly through the heads. Unfortunately even the best of joins caused a blip in the recorded sound and sometimes damaged the precious pole pieces. In 1945, the war over, a BBC research engineer went to Germany and returned with the compact portable Magnetophone at which we gazed with astonishment and envy. The Germans used lightweight plastic tape impregnated with ferrite.

Next day my RE tutor pronounced me 'Competent' and I did my first unsupervised tape recording. A young singer called Vera Lynn had devised a programme entitled 'Sincerely Yours'. Between each of her songs, she read out personal messages from family and friends in the UK to servicemen stationed in war zones across the world. This was recorded on disc so that if inadvertently any of these messages revealed to the 'enemy' the location of a particular service unit, they could be removed. My tape was a back-up to this process. Soon, Important People described the programme as 'too sentimental and bad for morale' and wanted it taken off. Together with our people on night shift who had repeatedly to play this same programme throughout the night, across the 5 Time Zones, we felt the same. However when we heard that "Thank You" letters were pouring in from the deserts of North Africa to the jungles of Burma for 'Dear Vera' from her 'Dear Boys,' we accepted the soldiers' verdict. It was also gratifying that our work served some purpose.

Classical Music and the Philips-Miller Recorder

The loss of the Queen's Hall required a whole re-think by Henry Wood about the continuation of the Proms. The Albert Hall, despite its size and notorious echo was the only alternative location. The London Philharmonic and London Symphony Orchestras would share the season with the BBC SO and conductors Adrian Boult, Basil Cameron and later Malcolm Sargant would assist Sir Henry. A trial season in the 1941 summer had surprised every one by its success. The Albert Hall was packed to the limit and despite a notice saying 'In the event of a siren alert, those wishing to go to shelters, please leave the hall quietly. Public shelters are available etc.' I don't think anyone left.

Classical music seemed to supply a necessary need in those days as evidenced by the huge success of the spontaneous daytime concerts organised by the pianist Myra Hess in the National Gallery, many of the audience in uniform. Despite having their ranks depleted by the 'call up', orchestras played in any undamaged space to full houses, borrowing players from each other if needed. The weekly BBC SO concert was not yet recorded for use on the Overseas Service because of the unreliable quality of short wave transmission. Reporters told us however that it was received and listened to in Europe and North Africa. The Phillips-Miller film system was used for all classical music recording.

On that memorable day when as an assistant I learned the know-how of this system, I found that prior to recording a greater amount of pre-preparation was required than for disc or tape. Facing me in that cramped room was a unit containing two combined machines placed side by side to form a complete channel capable of unlimited continuous recording or reproduction. Running at 32cm/sec about 15 minutes of music could be recorded on the first spool and then, with instant start up time, a switch easily changed over the incoming sound to the adjacent machine. Both machines were prepared in advance. The associated electronic apparatus was housed in a nearby bay.

Related page

For BBC use, the advantages of the Phillips-Miller system compared with the other two were, it had better sound quality, responding up to 8Khz and with no surface noise; it could easily be edited with scissors and plastic adhesive and change over from one machine to the other was a simple switch, whereas getting the motor of the Marconi-Stille up to full speed required the operation of a clutch and three gears for which a time allowance had to be made. As with tape, playback during recording allowed the quality of sound to be compared at any time. If the sound indicated that the sapphire had lost its sharp edge it could be replaced when the other machine was in action. There was something of a crisis developing in the increasing shortage of useable sapphire cutters. The Philips-Miller recorders having been obtained in 1938 from the designers in Eindhoven Holland, spare parts including the cutters were no longer obtainable. Two BBC research engineers, by now experts in 'Make Do and Mend,' solved the problem by making enquiries among the many Dutch refugees in London and found two with experience in diamond cutting skills. These two were hastily set up in a spare room in MV, a useable grinding lap etc. found and soon we had a source of BBC produced sharp cutters!

Some other programmesMy next experience with film was with a recording of the 'Brains Trust', another very popular weekly evening broadcast in which a resident panel discussed topics suggested by the listeners. The resident panel consisted of Professor Julian Huxley, naturalist and a member of the famous Huxley dynasty, C E M Joad, Professor of Philosophy, Malcolm Sargant, music conductor, and Commander Campbell who had world wide experience in the Merchant and Royal Navy from the days of sail to the present day. The excellent chairman, Donald McCulloch kept the discussions always to the point. The BBC code prohibited discussion of topics such as Religion and thankfully, Politics, and of course no Advertising, which was why the programme was recorded first on film so that it could be quickly edited should any of the panel unwittingly be indiscreet.

At this time also, a producer called Mr Roy Plomley had a strange idea for a weekly series in which well known people were isolated on a desert island with eight records of their own choosing. As no mention was made of how they were to be played, we concluded that it would be a 1920s wind up gramophone. Lacking a supply of steel needles, thorns could be used. The BBC record library of commercial records, the biggest in the UK, had been removed to a 'safe' place and the librarians had some trouble locating the ones chosen. It was part of a JME's job to play commercial records when needed but they were not pleased at having to find two minute excerpts and play them at the right moment in the interview. A lot of the yellow waxed crayon was used on grooves. Pre-recorded on film for editing, a trial broadcast produced very little reaction we did not expect the series to be continued.

Coming up to December we were occupied in preparing for the traditional Christmas 'Round the World' broadcast which would end with a speech by King George. For this special day a small group of Outside Broadcast engineers in saloon cars equipped with a small version of our disc recorder, toured the UK, recording Xmas messages from hospitals, ARP units, service canteens etc. which then came to us for editing. OBs in two white vans similarly equipped for disc recording, were operating in the Middle East, their recordings being flown to the UK from Cairo.

At this point I want to pay tribute to the unsung heroes of our recording section. From all the areas of action, as the War Reporters supplied the BBC with their 'on the spot' graphic accounts of the fighting, Edward Ward, Frank Gillard, Chester Wilmot, Richard Dimbleby, Wynford Vaughan Thomas and others became names on everybody's lips. But did any one know the names of the OB engineers who each shared all the hazards of the reporter whom they accompanied? It was their job to pilot the mobile recording van, find sources of power, record the War Reports on the disc recorder and some how find a means of getting the discs back to London. Gradually they obtained respect and valuable assistance from the Services Signals Corp, and even that of Montgomery himself. They had a base in one of the rooms in our corridor so we often had a chat when, in their army uniforms, they flew back for fresh supplies.

Arriving on shift at 4pm on December 6th, our SRE met us with "Ladies get everything on immediately - the Japs have bombed the US Navy" and thats what we did. We were two oldie WOs and one just newly trained and one RE. The next few hours were hectic. I was managing tape and when possible, helping with disc. At 11 pm we had a surprise visit from the Boss, SE[R] himself who asked the SRE what staff he had. He replied, "These ladies are doing splendidly!" The nightshift came on at midnight and we just went on working until the morning shift arrived. 'Double shifts' became common in the next few days and led to me getting a criminal record. Returning to my abode at 5pm I collapsed into bed. I was awakened by the landlady who said there was a policeman at the door complaining about the blackout. Sure enough, my bedside lamp was on and the window blackout was not in place. Summoned to appear at the Magistrates Court, the woman magistrate asked me what excuse I had. "I was very tired" I said. "Aren't we all" she said "Guilty. Fined £5". The policeman who had given evidence that he had "-- seen a light coming from a 4th storey window which could be seen etc --" showed me where to pay the £5 and my father sent me a postal order for £6! One night during a lull, the SRE told us to go and have a couple of hours rest on the First Aid room bunks as we had to be ready for Churchill addressing the US Congress at 4am. We fell asleep and were suddenly wakened by the SRE who had also dozed off. There were just ten minutes for preparation and we managed but it was a near thing!

Somehow or other the Christmas Day programme got put together and went out as usual with King George's speech at the end. The news received earlier that morning that Hong Kong had fallen to the Japs was deemed best postponed till the next day.

Dark days The months that followed probably saw the blackest time of the whole war. The daily schedule with its list of recordings to be done of 'Dispatches' from places in the Far East, acquired a succession of black cancellation lines. These made us unpleasantly aware of the speed of the Japanese advance, culminating in the fall of Singapore on 14 February 1942. We recorded on the night before and the reporter said "We can hear the guns across the Causeway so this will be our last report". Days later, the Prince of Wales, our newest and biggest battleship was sunk off Singapore. An RE and I were in the canteen for a meal and sat down at a table where a Control Room WO was already sitting. Suddenly she said "My brother's on that ship". She must not yet tell her parents! This was typical of the peculiar life we women were leading. We were having a 'safe' war enclosed in our windowless cellar. World changing events were taking place and, solely by voices heard through headphones and loud speakers, we were some of the first to hear the uncensored news, yet all we did was a repetitive job and eat and sleep. A few things would be preserved for history but most of our output would be scrapped a week later to enable more of the same.

Through the spring of 1942 we recorded only reports of retreats, defeats and losses. Tobruk fell. Rommel was chasing the Eighth Army almost to Cairo. There was a stalemate outside the great Russian cities where two huge armies were killing each other and dying in the snow. Submarine attacks with the loss of vital supplies and hundreds of sailors was at its peak and rations were reduced. Air raids on London were fewer but coastal towns like Hull and Plymouth were devastated. News coming from our newest ally, the USA, indicated that it was in a state of shock as week by week its armies retreated from its Pacific bases. It would take a year before its great industrial power could be activated. The BBC News was true but somewhat understated. 'A Northeast town was attacked by enemy bombers and sustained some damage and loss of life' was not quite the full story. Often, on our way back from the canteen, if we heard music coming from a studio we would creep in for a few minutes and listen. On one particularly depressing day I crept into Studio 4 and found the resident quartet, the Griller, was rehearsing the last movement of Beethoven Op 135. Suddenly the recollection of Beethoven's Muss es sein? Es muss sein! - Shall it be? It must be! and the poignant theme, hit me. A few tears made an appearance. This was embarrassing as in our male establishment any show of emotion produced exchanged glances and a muttered 'Huh. Women!'

Shostakovich's Seventh Symphony One day in June, the morning shift said that the London Symphony Orchestra, not the BBC SO were in Studio 1. Henry Wood was conducting. All day they had been recording bits of the rehearsal for him. It was to be broadcast on the Home Service this evening with an audience present. Someone had just seen a trolly of posh looking sandwiches being wheeled into Studio 1. Our SRE revealed all. It was to be the first performance outside the Soviet Union of a new Symphony by Shostakovich, No.7 - an important event. About 7pm the guests, Mr Maisky the Soviet ambassador, Sir Stafford Cripps, former British ambassador to Russia, and important BBC executives arrived. We were all ready and waiting. The SRE himself would control the volume level and change-overs. The REs were on tape and film and we two WOs with the help of a JME were on disc. During the day, problems had emerged. The score in the form of 900 microfilm discs had been sent from Moscow to London in the Diplomatic Bag. One other score had been sent to the USA. Henry Wood, not the most modest of men, had built himself a reputation for 'first performances' of new works and was determined to be ahead of the USA. so an hour from 8pm to 9pm on the Home Service was quickly scheduled, and a second performance in the Albert Hall for a Prom in a weeks time. But, lasting 80 minutes, the work was too long for the one hour available and 9pm Big Ben was sacrosanct. The work must be cut or it would be 'faded out' before the end. At precisely 8pm we all went into action. We had an impossible task. Without a score the SRE had to cope with sudden fffs and ppps. If during Allegro passages no possible pause for a change over was found, in all the systems, two machines were activated together, recording the same passage for a few minutes in the hope that this would be solved on playback. In that long long first movement our discs piled up, taxing the skill of the JME who was labeling what he said had "all the same tune". As the clock approached 9pm the music came to an end and there was a general sigh of relief. We heard that in Studio 1, at the last bar Henry Wood said 'We've done it" as the clock ticked a few seconds to 9pm. He had not made any cuts - just left out a few repeats and speeded things up more than he liked! This was not going to be a definitive performance. We had all been to busy to gain any idea of the work but this was remedied in the following week when bits of it were played back over and over again. Henry Wood had found numerous faults in the score and these had to be corrected before the Prom. The reaction to the Symphony from the Music Department was not very enthusiastic. They thought it rather bombastic and too long. I did not hear the Prom but it seemed to pass without comment. The work may have been inspirational to the Russians but it did not seem to reflect 'our war'. I do not remember it being played again at that time by any other orchestras, perhaps because of the large forces involved. When in the following years I mentioned the 7th symphony to other musical friends who knew and liked the Shostakovich 5th and 10th, I was met with blank looks.

In fact the next time I myself heard it again was as one of a series performed by the SNO and Naemi Jarvie in 1980?. I believe it was played more often in the US and had acquired a lot of myths about it being 'smuggled out of besieged Leningrad'.

That late summer of 1942 produced some very good weather though we still automatically glanced up anxiously at the evening sky, disliking a clear sky or a Bomber's Moon. We had grown to like lots of clouds and fog. The News spoke of 200 RAF planes carrying out raids on the Ruhr and other German industrial areas which was cheering, except that the final coda that "three of our planes are reported missing" meant the loss of another 24 aircrew. German raids on the UK were less than they were.

We continued by day to send out 'Music While You Work', a non stop half hour of popular music with a steady rhythm to which the thousands of men and women in workshops and factories could tap their feet and sing and relieve the monotony of their jobs. We sent out the much liked comedies, ITMA etc. to all the usual destinations. The various war zones seemed to have reached a stalemate. The British army had been driven back to wiithin 70 miles of Alexandria and morale was low.

The BBC man in the North Africa was Godfrey Talbot, who with his engineer Skipper Arnell, was equipped with a 30 hundredweight khaki painted recording truck which they called Belinda in which they could live and record. Talbot had had a great deal of trouble with the censors in Cairo when he tried to send his reports. Suddenly he had a new voice to record, the clipped speech of a newly appointed general who valued publicity. So, on the 23rd October 1942, the British public heard the voice of Bernard Montgomery saying to his troops "The bad times are over.They are finished. We will destroy the Axis Forces. It can be done and it will be done". A few days later we received the recording of the actual sound of the 1000 gun barrage of such ferocity that many of the discs Arnell tried to cut were spoiled because the cutter bounced and dug into the acetate. For the first time, people at home could listen to the sounds of a huge battle as it progressed to the day when we recorded the bells which Churchill suggested should be rung everywhere, to celebrate El Alemein. We began to collect and record material for the 1942 Christmas Day programme with rather more hope than 1941.