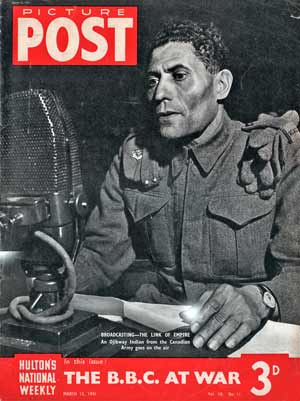

In its issue of March 15th, 1941, the magazine "Picture Post" published

an article about the B.B.C. at war. Here's the text and most of the photographs

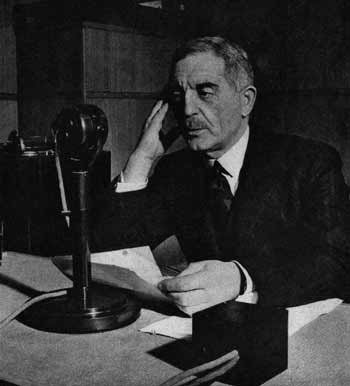

which accompanied it. It began with a couple of paragraphs by the Director

General, Frederic Ogilvie, who had taken over from Sir John (later Lord) Reith

in 1938. The main part of the article was written by Vernon Bartlett.

"Democracy is fighting for its life. British broadcasting has a vital part

to play in that fight, and it plays it without abandoning its standards.

It has not changed, and it will not change, its confidence in truth. The

broad principles of British propaganda are the only principles open to a

democracy which, in fighting for life, is fighting for freedom and the things

that make life worth while.

"The B.B.C. works in close co-operation with the Ministry of Information,

from which it receives guidance on all appropriate matters. The B.B.C. is

not itself a Government Department: it speaks authoritatively, but not necessarily

with the official voice. It presents British news and views to friendly

countries overseas. It carries truth across the barriers erected against

it in enemy and enemy-occupied countries. Working side by side with us here

are radio representatives of the various parts of the British Commonwealth

of Nations, and of the countries in Europe under Hitler's heel. Here too

are radio representatives of the U.S.A. The B.B.C. proudly regards itself

as the spearhead in Europe of free broadcasting for the world."

The B.B.C., even more than the Ministry of Food, the Ministry of Mines, the Ministry of Transport and the General Post Office, is unlucky in that almost every citizen in the country is affected by it and becomes its critic. If there is no coal, if the railways break down, if the telephones do not function, if the meat ration is not there, thousands of people make angry protests. But their protests are generally in one direction, and the Minister, urged on by them, gets busy and the situation improves. But if the B.B.C. programmes are bad, there are tens of thousands of critics, and the chances are that they are demanding progress in a dozen different directions. Also, especially since the air-raids began, more and more people sit at home and expect to be entertained by their loudspeaker.

In other words, I don't envy the heads of the B.B.C.. Still less do I envy the junior staff. Below buildings in and out of town, they have had to carry on their work since the blitz began; and I've spent too many nights on floors with my mattress almost touching the mattress of my neighbour, I've spent too many hours in basements and sub-basements and super-basements, to have anything but respect for the people who live there almost throughout the twenty-four hours.

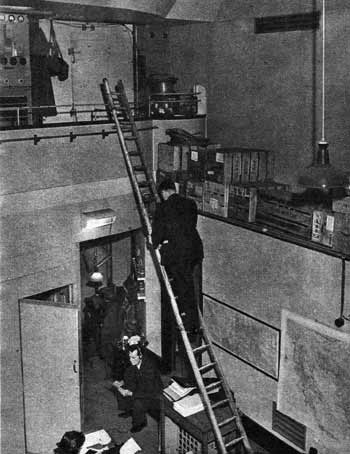

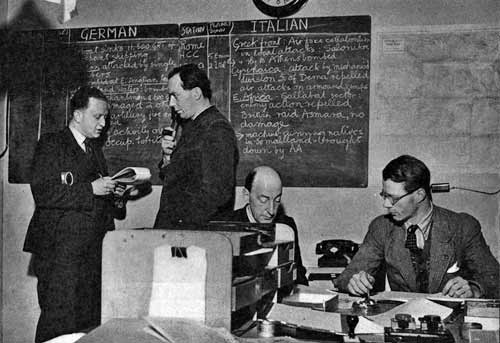

in the Home News Room

The Home News reporters work down below. The engineers' panel, files and stores are kept on the balcony. A ladder connects the two.

(this appears to be Studio BB - ed.)

If you visited Broadcasting House in peacetime you may have noticed, over the entrance, a large Latin inscription which, being interpreted, ran: "To Almighty God, this temple of the arts and muses is dedicated by the first governors in the year 1931, Sir John Reith being Director General. It is their prayer that good seed sown may bring forth good harvest, that all things hostile to peace or purity may be banished from this house, and that the people, inclining their ears to whatsoever things are beautiful and honest and of good report, may tread the path of virtue and wisdom."

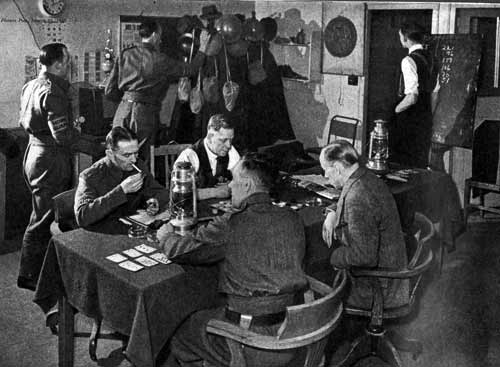

The Recreation Room of the B.B.C.'s Home Guard.

Enemy raiders make a special objective of the B.B.C. premises. The studios and offices are strictly patrolled by companies of the Home Guard, recruited by the staff, with instructions to shoot unauthorised visitors at sight. Extra men stand by as reinforcements in an emergency.

The B.B.C. has its own separate unit of the A.F.S.

They've been into action many times already.

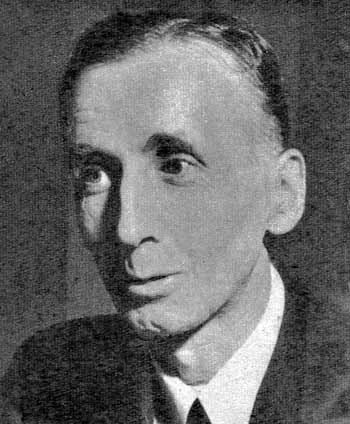

48 years old, Scottish, Presbyterian, Oxford Don, army captain in last war.

What have all these people to do with the programmes? In September, 1939, broadcasts went out in only nine foreign languages; they now go out in thirty-two, and even so the B.B.C. is at a disadvantage in that the Nazis have been able to take over the transmitting stations in so many countries that have come under their domination since the war began. Furthermore, for years of so-called peace, Dr. Goebbels and his large staff had spent thousands upon thousands every year in the propaganda that was designed to produce a Nazi victory and the disruption of the British Empire in a few weeks or months. Only now are the new B.B.C. transmitters coming into operation, which explains why, during the last few weeks, so many advertisements for new staff have appeared in the newspapers. The broadcasting day now consists not of twenty-four hours, but of over eighty-five.

There is, first, a service in English for thirty-one broadcasting hours. Had I the ambition to do so, I could listen to one of my own broadcasts to the Empire three times after I had spoken it into the microphone, for, in order to reach its audience at a good time in the evening, it is recorded and repeated at different times during the day or night until it has gone out in the North American, Eastern, African and Pacific services. And unless you have the almost incredible bad luck to be the victim of a gramophone needle that goes round and round in the same groove, you can be sure that no listener can tell to which area you have talked "live." In such a service, the news must be strictly impartial and must win a reputation for accuracy; the talks may contain the answers to Nazi propagandists, and the British have the initial advantage that their audience wants them to win and, in many cases, has sentimental memories of the towns that are damaged by Nazi bombers.

Then comes the Main European Service, which converts the B.B.C. canteens into places that remind you of the League of Nations building in Geneva. For twenty hours a day there are broadcasts in French, German, Italian, Dutch, and other languages of Central Europe. For another five hours there are broadcasts to the Scandinavian countries, the Balkans, Spain and Portugal. And here there is room for almost indefinite expansion; for even the Scandinavian countries have to be treated differently from each other. Norway fought, and is under Nazi domination. Denmark did not have a chance to fight, and is under Nazi domination. Sweden is still unoccupied, but is hemmed in economically by Germany. Finland is still unoccupied, but is more interested in Russia than in Germany.

You must carry it further. Even if the languages were the same, it would obviously be absurd to send similar programmes to the Germans and to the different countries that Hitler's men have overrun. The arguments that would encourage the Spaniards to resist Nazi pressure would be futile if used on the Jugoslavs. To many of these listeners, straight and impartial news is less important than fighting comment upon the news, for they are listening at considerable risk, and they need those arguments that will encourage them and those of their friends to whom they dare whisper the details they heard last night broadcast by the B.B.C.. One begins to realise why, in the offices of the B.B.C., you will find sub-editors on one shift poring over yards of agency tape while their predecessors of another shift are trying to make up for lost sleep on mattresses along the wall. These are the front-line trenches in the war of nerves.

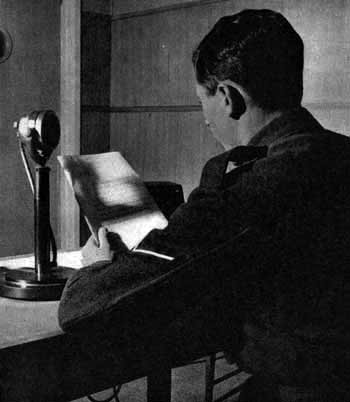

For obvious reasons, speakers to Germany broadcast anonymously. This speaker is an Englishman, educated in Germany. He is serving as a lance-corporal in the Army: has been lent to the B.B.C.

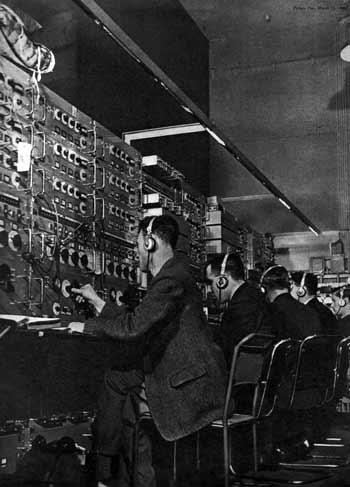

The Technical Brilliance

Which Makes Broadcasting Possible

From first to last, the whole work of

broadcasting depends upon the silent army of engineers who bend over switchboards and watch the controls. Hidden under ground, scattered throughout the country are the men on whom we rely to keep open the communication of the ether.

Even in peace-time the engineering department is one of mystery; I have now been broadcasting for fourteen years and have faced the microphone in fourteen countries and three continents, and I still do not begin to understand why my voice should traverse miles of space and dozens of brick walls in order to interfere with the privacy of your home. In war-time there are added complications in the life of a B.B.C. engineer, for the service must be maintained and yet the enemy aeroplane must not be guided by it to important objectives. It may mean more to you than it does to me to be told that the engineers have evolved a mechanism for checking wavelength accuracy to one part in ten million - oddly enough, there is a kind of live-and-let-live understanding about these wavelengths. In the old days the Union Internationale de Radiodiffusion, with its headquarters in Geneva, allocated wavelengths to all the European stations, with nine or ten kiocycles between them to prevent interference; despite the war, most stations still operate in their proper, stated ether lanes. The Germans or Italians sometimes jam the B.B.C.'s foreign broadcasts - the engineers call it "pesting" - but German controlled stations keep pretty regularly to their own frequencies.

The strangest apparatus at the B.B.C. is the standard of frequency apparatus, deep below the foundations of the building. Perched on a cushion of granulated cork is a thin sliver of quartz, held between two metal plates in a vacuum and connected so as to control the frequency of an oscillator which vibrates at 1,000 kilocycles per second. It thus becomes a yardstick for comparing wavelengths of any transmitters, and if you want to know more about it, please do not ask me. I prefer the human element in broadcasting.

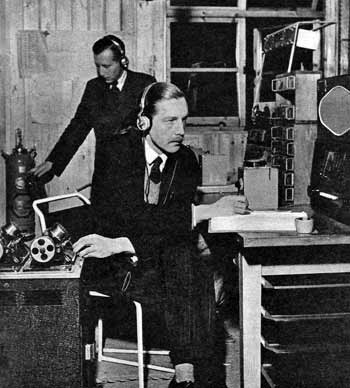

Broadcasting is only one side of the B.B.C.'s work. Listening-in is the B.B.C.'s job, too. A whole new department, called Monitoring, has been created to record what our enemies and the neutrals are saying.

This Monitoring Service, carried out at Government request, began in August, 1939, with a couple of men, who knew German and Italian, and a couple of secretaries. Its total staff now numbers hundreds and its 40,000-word daily digest is to be found in every office in Whitehall concerned with intelligence work or with propaganda. It is a most important weapon in the war of brains.

And, when all is said and done we come back to what is still probably the B.B.C.'s most important job - its service to you and me and its attempts to meet the demands of us, its critics in every home. Those attempts are genuine. There is a Listeners Research Bureau, with forty British Institute of Public Opinion research experts who interview a total of 800 people every day. In January 80 per cent. said they were satisfied; 10 per cent. were not; 10 per cent. had no particular opinion. I don't know in which category you would be. I might be in the first if there were no crooners and no theatre organ; you may be in the first because there are. And thank Heaven for our right to differ! One thing the B.B.C. must protect above all else is the presentation of the many-sided life of these islands. There have been attempts to treat it as the hand-maiden of every government department, and thus to rob it of colour and character. Within the last few weeks the influence of the Ministry of Information has been increased by the decision to attach two "advisers" to it. But the role of these advisers should be - I believe will be - less to direct it than to protect it from officials in other government departments who know a lot about their own jobs, but less than nothing about the all-important presentation of news.

Foremost among the B.B.C.'s war-time developments is broadcasting overseas. What progress are we making? What results are we getting? Here a B.B.C. official answers these questions.

In February of this year the entire Overseas Service, under its Controller, Sir Stephen Tallents, and its Assistant Controller, Mr. J. Beresford Clark, was re-cast. It now consists of six Services, which broadcast a total of fifty-four hours of programme a day. This is the latest, but assuredly not the final stage in an expansion which has been continuous from 1932, and has been greatly accelerated by the war. Development has meant much more than an increase in the number of transmitters, the number of hours of broadcasting, and the number of languages used. It has involved sustained effort to improve the quality of reception, to develop new types of programme, and to select and present material to suit the needs and tastes of special audiences, whether in Belgium or Brazil.

The stage is draughty. The night is cold. Dressed for comfort, not glamour, Ann Ziegler and Webster Booth sing love songs to the Empire.

John Citizen would probably be surprised to find that the voices of news-readers and others in the B.B.C. Overseas Service (which he himself has not heard) are as familiar to citizens in Sydney and Saskatchewan as are the voices of Messrs. Alvar Liddell and Frank Phillips to him. Yet it is so. Throughout the Empire the broadcasting authorities now pick up the programmes of the Empire Service and re-broadcast them from their own stations. In U.S.A. the B.B.C. news and talks are relayed by over a hundred independent stations, as well as by the many stations of the Mutual Broadcasting System. In U.S.A., J. B. Priestley has been the most popular of our broadcasters.

Each Empire Transmission contains two or more news bulletins, and news talks or commentaries. Second only to the news in importance are the talks, often grouped in a series such as "Britain Speaks" or "Democracy Marches," with speakers of the calibre of J. W Priestley and Wickham Steed. Other notable speakers - in addition, of course, to the Prime Minister and members of the Cabinet - are Vernon Bartlett, Howard Marshall, David Low, Robert Donar, Leslie Howard, Professor Julian Huxley, Pamela Frankau, and Thomss Woodroffe.

Many of the talks and programmes are addressed to a special section of the listening audience. "Calling New Zealand," for example, is a special talk in the Pacific Transmission, and "Songtime in the Laager" is an entertainment for South African and Rhodesian forces in East Africa. In "Canada Calls from London," Canadian troops in Britain take part in the show and send messages to their relatives. This series is handled by a unit of the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation working in collaboration with the B.B.C.

Alec Stuart, train driver, and Arthur Butterfield, bus driver, appear in the oldest regular magazine programme, "In Town To-night."

The main European Service of the B.B.C. now broadcasts for twenty hours a day. A second Service of five hours daily carries broadcasts for Spain and Portugal, the Scandinavian countries and the Balkans. The Director of the European Services is Mr. John Salt.

From the start, at the time of Munich, news has had pride of place. No matter what penalties the Nazis may impose, the peoples of Europe will try to satisfy their hunger for authentic news. It is on this fact that the success of the European Service is largely based. There is clear evidence that the B.B.C. broadcasts do get through. Surreptitious news-sheets based on the B.B.C. bulletins circulate from hand to hand among the oppressed peoples. It is significant, too, that the Nazis, having banned listening to the B.B.C., nevertheless go to great lengths to counter the B.B.C. in broadcasts to their own people.

In the European Services, some countries are given many other types of programmes to supplement the news. In the broadcasts to France, for example, the B.B.C. uses slogans, often set to the jingles of French nursery rhymes. Among the songs the B.B.C. has popularised in France is a devastating piece on Mussolini set to the tune of "Funiculi, Funicula." French wit has full play in daily discussions and dialogues, for the broadcasters are exclusively Frenchmen.

The broadcasts to Germany naturally contain many special features, including lists of prisoners' names. There are special broadcasts for Austrians, and special entertainment and news programmes for the German armed forces. The B.B.C. features in its broadcasts a radio character called "Frau Wernicke." She speaks in the Berlin equivalent of Cockney, and confounds the Nazis with their own arguments as she waits in a shopping queue or sits in an air raid shelter with her neighbours. A very different type of broadcast is given in the regular series, "Vormarsch der Freiheit" ("March of Freedom"), which dramatises themes of recent German history and the struggle to defeat the Nazi aggressor. Of the regular spokesmen of Britain to the German people, the best known is Professor Lindley Fraser.

Colonel Harold Stevens, born in Italy, formerly a member of the military attaché's staff at the British Embassy in Rome. He is responsible for five news bulletins sent to Italy daily, 75 minutes in all.

At the time of the collapse of France, the B.B.C.'s Czech and Polish broadcasts carried messages instructing Polish and Czech soldiers to keep in touch with the British Command. Czech pilots in France were told to fly their machines to Britain. To-day the Polish and Czech forces in Britain give frequent broadcasts, often of troop concerts, to their countries.

The B.B.C. now broadcasts to Latin America for four hours every night. As usual, news is the keystone of the programme schedule. The bulletins in Spanish and Portuguese, are regularly rebroadcast by a large number of stations in Latin America, where there is a good deal of listening in public places. Salvador de Madariaga, the distinguished Spanish scholar and statesman, has done regular broadcasts. British Cabinet Ministers speak at the microphone and their words are then read in translation. Recently the Lord Mayor of London told the B.B.C.'s Latin American listeners that, in spite of Nazi exaggerations, there is still plenty of life in London.

These listeners have been highly enthusiastic over a series of special feature programmes, some of which have dramatised great figures or events in the history of South America. Other features bring to the audience a picture of the great war effort of the people of Britain.

The highly specialised Near Eastern Service broadcasts for two and a quarter hours daily, chiefly in Arabic, but also in Turkish and Persian. The news is supplemented with talks and commentaries. The talks in Arabic often deal with cultural matters, such as Eastern literature or modern science. For music - the Arab music which sounds so mournful to Western ears - the B.B.C. makes much use of recordings specially made for it in Cairo by star singers and musicians.

On one occasion two members of the British Government - Mr. Amery and the late Lord Lloyd - spoke to our Turkish allies in their own language. This should kill for ever, in at least one country, the legend that the British are bad linguists.

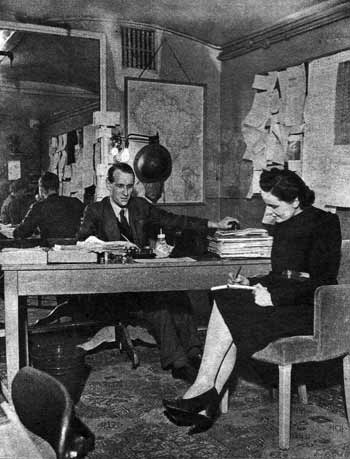

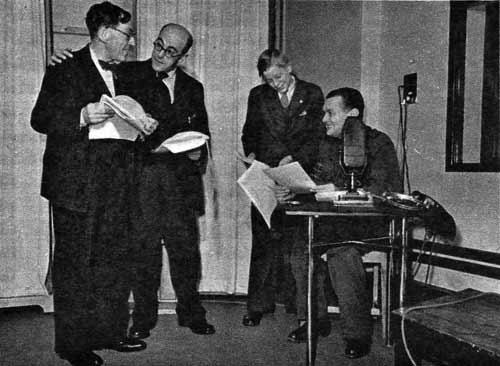

The monitoring staff listens-in to 220 news bulletins in 30 languages, and collates a million words a day. (In the foreground of this photo are Telediphone machines, which recorded on a wax cylinder. - ed.)

Thus, in "Listening Post," a short programme broadcast daily to North America, the B.B.C. quotes chapter and verse of assertions made by the Axis, and exposes the motives and technique of Goebbels. "Listening Post" recently showed, for example, that the arguments used by Germany to drive a wedge between Britain and U.S.A., are identical with those used a year ago to drive a wedge between Britain and France. Goebbels had altered the trimmings, but the model remained the same.

In this programme, as in all its Services, the B.B.C. remains faithful to the broad principles of British propaganda; principles which are poles apart from those of Hitler and Goebbels. Those principles are based on the view that in the long run truth is more effective than the lying technique advocated in "Mein Kampf."

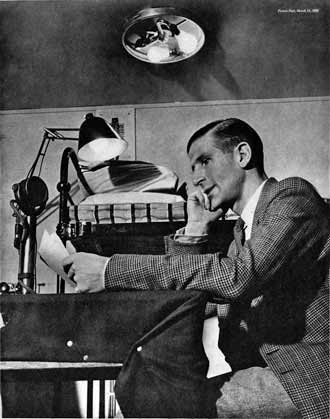

THE BROADCAST THE WHOLE COUNTRY LISTENS TO: The

Announcer Gives the News

And this is Alvar Liddell reading it. In an underground studio, with his bed beside him, is one of the men whose voice is heard in every home. Whether the news is good or bad, the calm friendly voice never varies. Even when the bombs are falling, it never fails. It is the voice of sanity.

A FRONT LINE TRENCH IN THE WAR OF NERVES:

Tin-hatted Laurence Gilliam Plans a Drama Programme Scattered throughout the country, working basements, dossing down on the floor, the B.B.C. gets on with the job of filling the air with 85 hours of broadcasting time in 32 languages every day. Entertainment and news for the Home Front. Encouragement for our allies in enemy-occupied territory. Advice for the neutrals. Propaganda to the enemy.

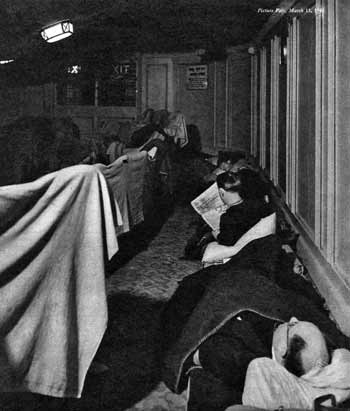

A Bedtime Scene

On the stage of the variety theatre, a show is being broadcast. At the back of the auditorium, B.B.C. staff snatch a few hours' sleep.

Checking-up on a Hundred Transmitters

Ceaselessly the monitor listens for the slip of a word which may reveal the enemy's intentions, news that may save thousands of British lives. |

Wartime Finds a Place for Women Announcers

Before the war, Elizabeth Cowell was one of the two original television announcers. Now she announces women's interest programmes.

A Film Star Gives an Interview

Ann Dvorak is interviewed by Presentation Director, John Snagge. Waiting his turn in the background is Mr. Anthony Pelissier, the actor.

The Most Popular Wartime Programme

Vic Oliver, Bebe Daniels and Ben Lyon in "Hi Gang." This show gets one of the biggest fan mails of any regular B.B.C. feature.

John Watt Works Where He Washes

The director of variety's office is a hotel bedroom. Discussing a new show with him is chief variety producer, Harry S. Pepper, wearing the official war service badge.

Shows are Planned in a Theatrical Dressing

Room Sleeping in the Royal Box, working in the star's dressing

room, Cecil Madden plans musical shows for the Empire in an empty

theatre.

|

|

How We Know What Our Enemies

Are Saying: A Monitor Reports a Vital News Flash to His Editor.

Important news, picked up by the monitors on their radio sets, is reported to the editors, who record and precis the material into a daily digest which is circulated to the war leaders. When war began, nobody paid much attention to the monitors. Now they are a vital part of our intelligence system. |

The Hours of Rehearsal Before the Broadcast

The Laurence Turner String Quartet have a rehearsal. One-eigth of broadcasting time in the home programmes is devoted to serious music; one-half to light music and entertainment.

|

Uncle Mac Broadcasts in Uniform

Wearing his Home Guard uniform, Derek McCulloch directs a rehearsal for the Children's Hour. |

A Session for School Children

Every mood, every class, and every age is catered for in the day's programme. Ann Driver shows schoolchildren how to keep fit.

|

THEY'RE ON THE AIR:

The Acting Which the Audience Doesn't See Producer Harold Rose is on the right. He is directing the actors in a play called "Three Men on a Raft." It is one of the five hundred plays and features which the B.B.C. drama department puts on the air in the Home and Forces programmes every year. |

HOW THE B.B.C. KEEPS OUR SPIRITS UP: A Variety Show for Munition Workers

After the news, variety entertainment has the largest number of listeners The B.B.C. issues free passes to the audience - in wartime, usually members of the Services or factory workers - who contribute to the broadcasts with their applause and help the artists with their laughs.

|

OUT IN THE PROVINCES THERE'S COMMUNAL LIVING:

To Save Expense a Home is Shared

Some of the B.B.C.'s evacuated staff go into billets. Some put up in country pubs. Some - like members of the Drama Department shown in the picture - take over private houses, live communally. Here Marianne Helweg, play adapter, serves a meal to producer Stephen Potter. Sitting on Potter's left are Mary Allen and Laurence Gilliam. |

The B.B.C. Has Opened Its First Bar

Never before has alcohol been sold on B.B.C. premises. But the rule has been relaxed in the country club.

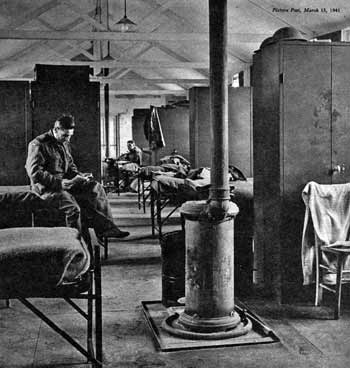

And One of the Wartime Dormitories

Every station has its own dormitories. This one is used as a barracks by the Home Guard. For twenty-four hours a day they keep armed watch on gates, offices, studios and transmission stations. |

A Typical B.B.C. Billet in the Country

Some of the staff take "digs" with the local residents. A few live in hotels. The majority rent a house and mix in together - but not many of them are lucky enough to find a cottage like this.

Country Radio Stations Are Equipped

Like Small Towns This specially-built hut has, beside a sick ward, dormitories, clinic and a communal lounge. |